Trump’s tariffs and a tale of three human-made global shocks

In terms of their impact on the international trading and monetary system, Donald Trump’s reciprocal tariffs are comparable to Richard Nixon’s 1971 dollar devaluation and Paul Volcker’s 1980s' interest rate hikes

Former President Richard Nixon (left) & US Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. (Source: NYT)

Former President Richard Nixon (left) & US Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. (Source: NYT)US President Donald Trump’s unilateral tariff impositions — 10% (at present) on goods imported from most countries and 145% from China — are comparable, for the scale of shocks unleashed and transformation engendered to the international trading or monetary system, to two other actions initiated by powerful men.

The first was by a former president and the second by a central banker, both also from the US. The worldwide economic disruptions resulting from their actions were, just as Trump’s, unlike those caused by impersonal forces (the 2008 Global Financial Crisis), or pathogens (the Covid-19 pandemic or the 14th century ‘Black Death’ bubonic plague).

The Nixon Shock

The two decades following World War II, roughly from 1949 to 1969, were a relatively benign period for the global economy, with no major panics, crises, hyper-inflations, or recessions.

Those seemingly good years — more so after two world wars and the Great Depression (1929-1939) sandwiched in between — were, to a great extent, underwritten by the so-called Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates.

Under it, countries were required to maintain their currencies within plus or minus 1% of a pre-determined exchange rate against the US dollar. They would maintain this parity by intervening in the foreign exchange market — selling dollars when their currency was weakening (depreciation) and buying in the event of strengthening (appreciation). The dollar was, in turn, convertible to gold at a fixed rate of $35 per ounce.

With all currencies freely convertible and pegged against the dollar, and the US committed to backing every dollar overseas with gold, it translated into a virtual system of fixed exchange rates. The system worked so long as the US had enough gold, which it was obliged to offer at the fixed price to any country demanding the exchange of its dollar reserves with the yellow metal. In 1947, the US had accumulated around 70% of the world’s gold reserves.

That changed by 1966, when the over $14 billion of the dollar currency reserves with the central banks and governments of other countries exceeded the United States’ own $13.2 billion worth of gold holdings. Moreover, only $3.2 billion of that was available to cover foreign dollar holdings, with the balance needed to back the domestic issuance of currency. Thus, the US was in no position to honour its obligation to deliver gold in exchange for even a quarter of their reserves held in dollars.

On August 15, 1971, the then US President Richard Nixon unilaterally — like Trump — ordered the “suspension” of the convertibility of the dollar into gold. With foreign governments and central banks no longer able to exchange their dollar reserves for gold, it marked the beginning of the end of the Bretton Woods regime.

In December 1971, the dollar was devalued against gold to $38 per ounce. Other leading industrialised countries agreed to revalue (appreciate) their currencies. The net effect was a 10.7% average depreciation of the dollar relative to these currencies. But even this new set of fixed exchange parities vis-à-vis a devalued dollar couldn’t hold. As gold prices, a barometer of uncertainty, soared to $90 an ounce in early 1973, the dollar came under speculative attacks. Towards March 1973, nearly all key currencies were floating against the dollar.

The Nixon Shock effectively inaugurated the era of unstable floating exchange rates and “fiat” government-issued currencies not backed by gold or any other solid physical asset. The value of any currency and its exchange rate was, henceforth, based on the public’s (including global investors’) faith in its issuing country.

The Volcker Shock

The dollar’s devaluation and end of Bretton Woods were followed by two cataclysmic events, both linked to oil.

The Yom Kippur War of October 1973 led to an oil embargo by Arab producing countries against the US and other western nations supporting Israel. Iran’s Islamic Revolution of 1978-79, likewise, pushed up international crude prices.

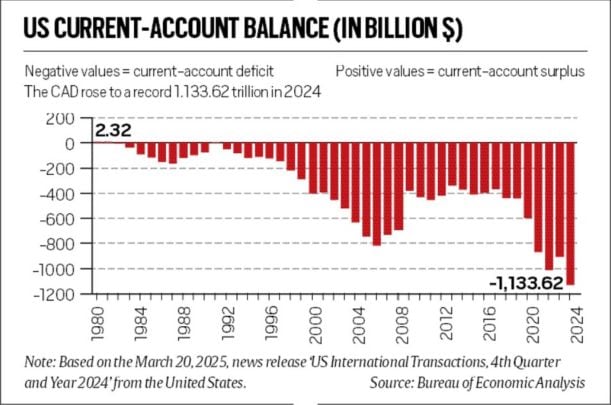

US current-account balance

US current-account balance

In the US, average consumer price inflation rose to 11% in 1974 and further to 11.3% in 1979 and 13.5% in 1980 — a far cry from the 2.2% over the fifties and sixties.

That was when Paul Volcker, appointed as Chairman of the US Federal Reserve under President Jimmy Carter in August 1979, entered the scene. Volcker substantially tightened the US central bank’s monetary policy and hiked its target “federal funds” interest rate, which reached 13.8% in December 1979. It peaked at 20% in June 1981, by which time Ronald Reagan succeeded Carter as US President.

The Volcker Shock helped bring down US inflation to 3.8% at the end of 1982. But the federal funds rate remained elevated even after that — within a 6-11.5% range and at 9.1%-plus in January 1989, when Reagan left office.

The reason Volcker kept interest rates high was simple. Under Reagan — a Republican, like Nixon and Trump — the US government massively stepped up defence spending while simultaneously slashing tax rates. The result: the federal budget deficit ballooned from 2% of GDP in 1980 to 6% by 1985. Volcker, then, had to continue with his tight-fisted monetary policy to offset Reagan’s expansionary fiscal measures.

What the high interest rates, however, also did was attract foreign funds into the US. These inflows boosted the value of the dollar, eroding the competitiveness of US exports and its manufacturing sector. The global economy was reshaped around the US that acted as a giant magnet for exports from the rest of the world, especially China.

The accompanying chart shows the US recording current account deficits (CAD) on its external balance of payments every year since 1982, save 1991. The CAD crossed $1.1 trillion in 2024. The US could run and finance these large deficits purely on the strength of the dollar’s status as the world’s “reserve currency”. That confidence and trust in the dollar was enabled by the high interest rates during Volcker’s tenure at the US Fed.

It’s another thing that the foreign money coming into the US mostly flooded its financial and property markets. They sowed the seeds of the credit-cum-asset price bubble in the run-up to the Global Financial Crisis, while also hollowing out the country’s manufacturing base. The flip side of US deficits was China’s extraordinary economic boom.

Cut to the present — the Trump Shock

Trump’s “reciprocal tariffs” neither address inflation nor the dollar’s overvaluation, which the Volcker and Nixon shocks did.

What they seek to address are the United States’ twin deficits — fiscal and CAD. The tariffs are supposed to provide revenues to the US Treasury and also increase “negotiating leverage” to force other countries to open their markets to American exports. Tariffs are also expected to result in re-shoring, particularly of high value-added manufacturing, bringing factories and jobs back to the US.

“We will supercharge our domestic industrial base [and] pry open foreign markets,” Trump has said. Parallelly, his administration is planning to push major trading partners to appreciate their currencies to improve US export competitiveness.

The Chairman of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, Stephen Miran, has floated the idea of a ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’. It is similar to the Plaza Accord of September 1985, where France, West Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom agreed for a depreciation of the dollar relative to their currencies.

“It is easier to imagine that after a series of punitive tariffs… Europe and China [will] become more receptive to some manner of currency accord in exchange for a reduction of tariffs,” Miran wrote in his now-famous ‘User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System’ essay of November 2024.

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Apr 20: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05