US vs China. Anatomy of Global Economic War

World markets are in a fever pitch: President Donald Trump's introduction of a new system of tariffs against most countries has led to expectations of a global recession and a collapse in global trade. What is the reason for such drastic changes in the global architecture?

At the end of last week, stock markets in the United States reacted to the global agenda and the threat of a global recession with a massive collapse. Tthe probability of the recession in the US was raised from 30 to 45 percent. In two days, the key US stock indices fell by a cumulative 10 percent (5 percent per session), losing a total of about $10 trillion in market capitalization. Therefore, all attention was focused on trading on Monday and Tuesday, April 7 and 8. The continuation of the negative trend could have raised investors' fears of a global crisis similar to the 2008 collapse.

On Tuesday, April 8, the S&P 500 index started with an increase to about 5,200 points, moved downward after a certain rebound and rebounded again after the news of a 90-day “tariff pause.” Other key US stock indices are experiencing a similar fever.

Why the US is winding up the global liberal project

Imagine that after World War II your economy accounted for 50 percent of the world's total. But in order to win the Cold War, you had to share a part of the economic pie with your allies.

The US shared it with Japan and Germany. Then it shared with South Korea. Then it decided to break China away from the USSR and gave it a significant segment of the American market.

Today, the trade imbalance between the US and China is a key factor in the first Global War, which is gradually spreading around the world.

By the way, back in the 1970s and 1980s, America talked not about the “Chinese” but about the “Japanese” threat: many films were made and articles were published, sounding the alarm that the Japanese would end up buying all the assets in the United States and defeat them economically.

In both cases, the United States reproached its trading partners (China and Japan) for transforming the trade balance in their favor by mildly devaluing their national currencies (Japan did so in the 1980s, China has done the same since the 1990s).

In recent years, we have seen how China pursued a policy of gradual depreciation of the yuan. And the United States has always criticized Beijing for doing this artificially.

That is why the United States periodically raises the idea of artificially equalizing the exchange rates of the national currencies of its trading partners against the dollar.

An example thereof is the artificial devaluation of the dollar under the Plaza Accord in the 1980s, which involved Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and France. These countries agreed to devalue the dollar against their national currencies, i.e. to strengthen their own currencies.

The Plaza Accord was the point at which the US economy began to recover. In the 1980s, Japan almost caught up with the United States in terms of export potential. But after the Plaza Accord, things went in the opposite direction. Japan strengthened the yen and faced a whole bunch of problems: a sideways trend in GDP, i.e. almost zero economic growth, a deflationary trap, a crisis in the real estate market and the banking sector, an excessive rate of domestic capital accumulation and a huge shortage of domains attractive for investment.

Subsequently, the United States opened its market to Mexico, Turkey, Vietnam and other countries that needed to be “kept close.”

In the 1980s, in terms of GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms, the US economy accounted for 22 percent of global GDP, while China accounted for only 2 percent. The internal mechanisms of globalism have not yet revealed their essence to America.

The turning point occurred in 2015: the share of the US and Chinese economies in the structure of the global economic system was equalized (in terms of purchasing power parity). Now China is already ahead: it has 19 percent of global GDP in PPP terms, while the United States has 16 percent.

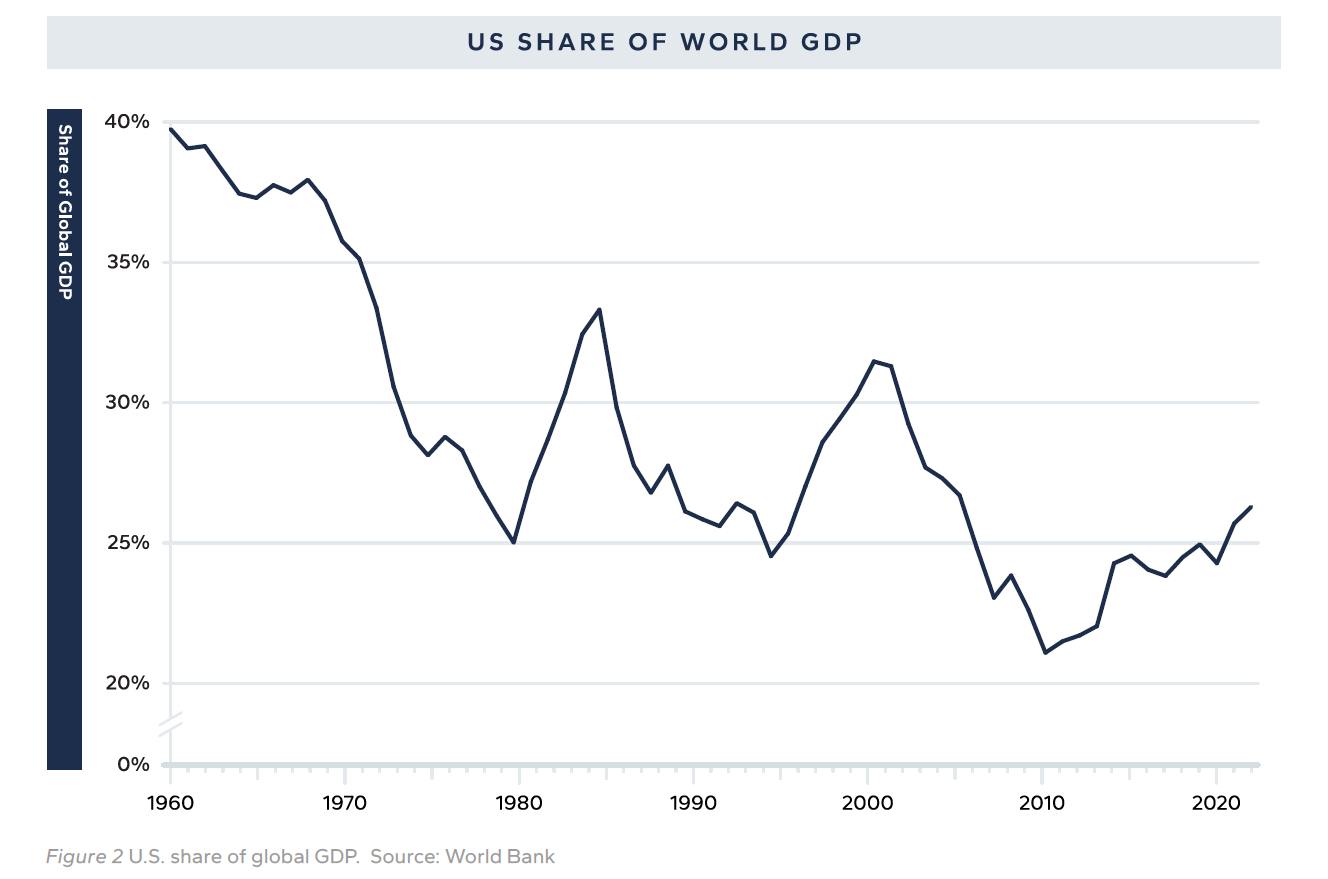

We can also estimate the share in nominal GDP, in which case the picture will be somewhat different: the United States has 26 percent and China ranks second with 17 percent. But even in nominal terms, the share of the United States in the global economy has halved since World War II!

If such a trend continues for another 10 years, China will overtake the United States even in nominal terms, especially if dollar inflation slows down: yuan inflation is half as much, so the acceleration of nominal GDP in China due to the deflator is weaker. In addition, the policy of weakening the yuan against the dollar underestates the currency equivalent of China's GDP in dollars. In essence, the United States is trying to get into the last car of the “global train” of its dominance in the world.

If the current dynamics continue, in 10–15 years the US will trail China in terms of nominal GDP, and its share in the structure of the world economy will be reduced to 15 percent in nominal terms and below 10 percent in PPP terms.

You can control technology, but hegemonic status determines the size of GDP. The size matters because defense spending is calculated on the basis of GDP, and the size of public debt and its servicing is correlated with GDP.

The size of GDP affects per capita income and wages, social policy and the capacity of the domestic market.

Today, America has simply started to save the conventional “pie” of the domestic market because many of its pieces have been taken by friends and partners.

In the short term, the introduction of new duties (America imposed 125% duties on China and the PRC imposed 84% duties on the United States) will result in a crisis of overproduction, overstocking and deflation in China.

In the US, there will be a shortage of a number of goods, as was the case recently with eggs, and inflation.

Both China and the United States are experiencing a sharp slowdown in GDP growth, but the brake on growth is longer in China (5 percent) and shorter in the United States (2.5 percent).

Global commodity prices (oil, metals, agriculture) have plummeted. Global value chains are being destroyed. Cooperative technological chains between countries are being dismantled. World trade and global GDP growth are slowing down. Financial markets are experiencing a crisis.

Current events are very reminiscent of Black Monday in 1987, when markets instantly fell by 22 percent. Afterwards, the depth expanded to 30 percent, interrupting a long bullish trend.

Back then, the crisis originating from Wall Street did not destroy America. It crashed oil prices, collapsed global trade and destroyed the USSR.

This time, the arrow of the Wall Street crisis is pointed toward China. But, unlike the Soviet Union, China has been preparing for these events.

In the 2018 feature film Default about the beginning of the financial crisis in South Korea in 1997, when the economy was doing well. There is a scene where an ordinary analyst at the country's central bank calculated the probability of the country's default, and this process turned out to be irreversible in her mathematical model.

Today, such an “ordinary” analyst is the American economist Stephen Miran, who has become Trump's chief economic adviser.

Last fall, he wrote A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. This document has become a textbook of current US policy.

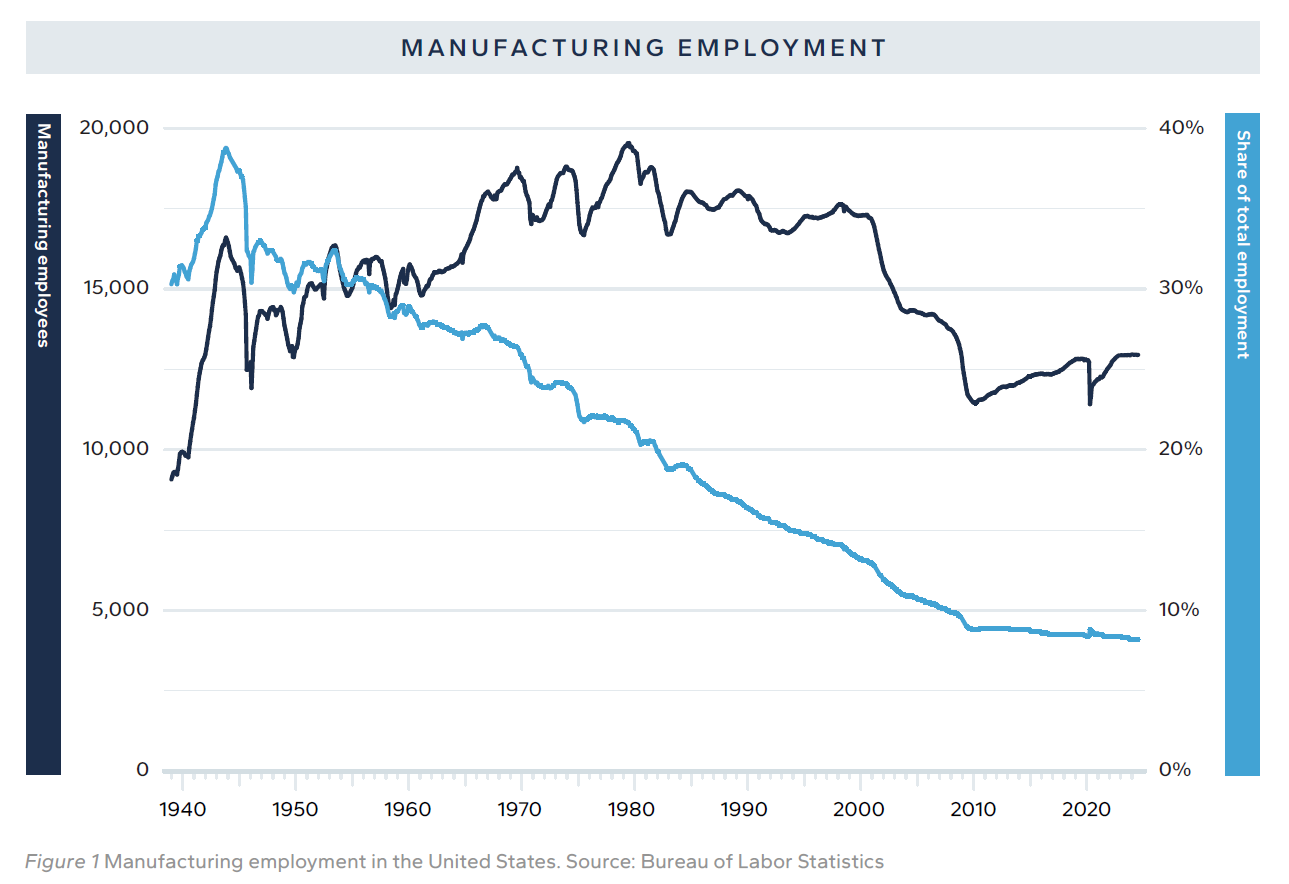

Here are two key charts from it.

The first one shows the decline in US industrial employment: from 30 percent of the population in 1940 to 8 percent in 2023. The second shows the share of US GDP in the global economy: a drop from 40 percent in 1960 to 27 percent in 2023 (although there was a drop to 22 percent in 2010). The recovery in recent years is a consequence of dollar inflation and Fed money issuance after the 2008 global financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic.

Another important graph by Stephen Miran is the dynamics of the current account of the balance of payments, which in the United States is largely formed by the balance of trade in goods.

After a surplus in the 1960s and 1970s, the deficit has sharply increased, reaching one trillion dollars and 3.5 percent of GDP.

In absolute terms, this is a historical anti-record. In relative terms (to GDP), it was even worse in the early 2000s (6%), but the current improvement was achieved again thanks to dollar inflation and Fed money issuance. In other words, in today's monetary paradigm, the relative indicator would begin to deteriorate sharply to 6 percent of GDP and beyond.

In particular, Stephen Miran describes the reasons for the key imbalances in the US balance of payments and trade by referring to the Triffin’s dilemma, which covers the following contradiction: why is the dollar so popular in the world against the backdrop of US trade and budget deficits?

Miran believes: “The deep unhappiness with the prevailing economic order is rooted in persistent overvaluation of the dollar and asymmetric trade conditions. Such overvaluation makes US exports less competitive, US imports cheaper, and handicaps American manufacturing. Manufacturing employment declines as factories close. Those local economies subside, many working families are unable to support themselves and become addicted to government handouts or opioids or move to more prosperous locations. Infrastructure declines as governments no longer service it, and housing and factories lay abandoned.”

The problem is compounded by the reversal of Fukuyama's end-of-history theory and the return of national security threats.

Having no serious geopolitical rivals, US leaders believed they could minimize the significance of the decline of industrial enterprises. But with China and Russia, with their powerful and well-diversified manufacturing, posing threats not only to trade but also to security, the American industrial sector is once again in need of recovery.

If you don't have supply chains that can produce weapons and defense systems, you don't have national security. As President Trump said, “If you don't have steel, you don't have a country.”

Miran very accurately identifies the main reasons for this situation: the ever-increasing demand of the world's central banks for the dollar as a key reserve currency. This demand has led to the accumulation of dollars in the reserves of dozens of countries and a significant overvaluation of the real exchange rate of the dollar against the currencies of other countries. According to the IMF, there are about $12 trillion of global foreign exchange reserves in official hands, of which roughly 60% are allocated in dollars—in reality, reserve holdings of the dollar are much higher, as quasi- and non-official entities hold dollar assets for reserve purposes too.

Clearly, $7 trillion of demand is enough to move the needle in any market, even currency markets.

For reference, $7 trillion is roughly a third of U.S. M2 money supply

Miran's key conclusion is as follows: “The interplay between reserve status and the loss of manufacturing jobs is sharpest during economic downturns. Because the reserve asset is “safe,” the dollar appreciates during recessions. By contrast, other nations’ currencies tend to depreciate when they go through an economic downturn. That means that when aggregate demand suffers a decline, pain in export sectors get compounded by a sharp erosion of competitiveness.”

Miran believes (see ZN.UA's information sheet below) that the devaluation of the yuan, yen or euro against the dollar will compensate for any tariff barriers from the US. In other words, the change in the exchange rate and the tariff almost completely offset each other.

ZN.UA information sheet

This mechanism can be illustrated as follows.

Let’s assume that

px is the price of goods supplied by foreign exporters, denominated in the foreign currency of such an exporter,

e is the exchange rate (of dollar to foreign currency),

τ is the tariff rate.

The price paid by (US) importers is:

pm = e(1+ τ )px.

Suppose we start with e=1 and τ=0. The US government imposes a 10% tariff on imports, and the foreign currency of the trading partner also depreciates by 10%.

The price paid by importers in the US is then:

Pm = 0.9(1,1) px = 0.99px.

This trick was actively used by China, which devalued the yuan to compensate for tariffs on imports of its goods to the United States.

So, according to the Trump team, only shock tariff therapy, implemented not only against China but also against other trading partner countries, can remedy the situation with the US trade deficit, the budget deficit and American industrial production.

But this is not the end of the story

According to the Miran model, the tariff step alone is not enough.

The next step is a coordinated revaluation (strengthening) of their national currencies, primarily the yuan, euro and yen, by the central banks of the countries that are trading partners. Something similar to what Japan was forced to do in the 1980s as part of the Plaza Accord.

However, the central banks of other countries may refuse to do so. In this case, the United States will again have to resort to geopolitical coercion.

According to Trump's new doctrine, a country that has no industrial production is not a country, but a territory.

Please select it with the mouse and press Ctrl+Enter or Submit a bug

Login with Google

Login with Google