ExplainSpeaking: what is the ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’ and dollar devaluation plan, why

To turn around the United States’ trade deficit, Donald Trump has two policy options: imposing tariffs on imports or devaluing the US currency. Here’s what the second option entails, the likelihood of it being exercised, and its possible impact.

A US dollar in one's pocket goes a long way in most other countries. (Reuters/Dado Ruvic)

A US dollar in one's pocket goes a long way in most other countries. (Reuters/Dado Ruvic)Dear Readers,

Last week’s ExplainSpeaking attempted to make sense of Donald Trump’s economic policies.

This week’s edition should be read as an extension of the same but with a crucial difference: last week, we focussed on what the Trump administration was trying to achieve, and the biggest policy tool they have used until now — import tariffs — and their initial repercussions.

This week the focus is on the other policy option that the Trump administration has — the devaluation of the US dollar — an option that many believe is likely to be used soon.

First, some context

Let’s take a step back to first understand what President Trump is trying to achieve: to turn the US into a manufacturing superpower (or at the very least, address the massive trade imbalance that exists at present).

To be sure, the US posted an over $1 trillion trade deficit in 2024. In other words, the total value of goods imported (from the rest of the world) by the US was $1 trillion more than the value of the goods exported (to the rest of the world) by the US. Further, 2024 was reportedly the fourth consecutive year when the US clocked a trillion dollar trade deficit.

This weakness in trade is not a new thing for the US; indeed, the US has run a trade deficit for decades, albeit not always this large. Also, an ever widening trade deficit means that the US barely manufacturers goods inside the US, which, in turn, implies lower levels of job creation in the US.

President Trump ran and won the election last November on the promise that he will turn around this situation, which he characterised as one where the rest of the world was ripping the US off.

Now, the fact is that, notwithstanding these historic trade deficits, the US has also had historically low unemployment rates. So arguably, the main issue isn’t more job creation; the central goals for Trump are more manufacturing inside and lower trade deficits.

Role of dollar’s exchange rate

Why do Americans import goods instead of buying from within the country?

For one, it is genuinely possible that nobody inside US may be making the product because of lack of skills (say a Madhubani painting) or lack of raw material (say potash, a fertiliser).

But there is an overwhelming reason: goods from the rest of the world are much more affordable. This is because of the US dollar’s strong purchasing power. A US dollar in one’s pocket goes a long way in most other countries.

And the reason for the US dollar’s exceptional strength: The trust it enjoys both as a store of value (that is, it won’t lose value) as well as a medium of exchange (that is, others will accept it) across the world — the two essential ingredients of any currency.

It is important to note that things like a strong economy, the independence of the central bank (US Federal Reserve) from government diktats, and the Fed’s commitment to maintain price stability are some of key reasons why the dollar doesn’t “lose value”.

In fact, this trust is so high that the central banks of all countries hold US dollars as their assets (foreign exchange reserves) or guarantees against which they issue their own currency — this includes India. Dollars make up 60% of all forex reserves in the world.

Further, 50% of all transactions are reportedly denominated in US dollars.

Since all countries love to hold on to US dollars and transact in them, the demand for dollars is high, and always going up. That implies its exchange rate with any currency continues to go up. This, in turn, implies the dollar has an increasing purchasing power and it makes sense for Americans to use it to import cheaper goods from the rest of the world.

How to become a manufacturing giant, reduce defecit

Given the strength of the US dollar, there are two main ways in which Trump could have gone about these goals.

- 01

Slap punitive tariffs on all its trade partners.

Either the higher prices of imports will reduce the demand for imports, thus bringing down the deficit or it would force foreign companies to set up shop inside the US, thus boosting domestic manufacturing and reducing deficits.

This is the approach Trump has been following but as the events of the past few weeks have shown, it could lead to several undesirable outcomes as well.

For one, even if the foreign nations don’t retaliate, costlier imports are costlier for US citizens, not the foreign citizens or companies.

If the tariffed nations retaliate and start a full-fledged tariff war, the hurt becomes manifold and is spread all around with everything becoming more costly and supply chains being disrupted.

It could also lead to tariffed countries resorting to “devaluing” their own currencies to negate the tariff. To do this, those countries can either buy US dollars and/or sell their own currencies in the open market, thus increasing the relative supply of their currency and bringing down its “price” (or exchange rate) relative to the dollar.

- 02

The US convinces the other countries to allow the dollar to lose value (devalue) relative to other currencies.

Imagine a scenario where other countries sold the dollars that they had in the open market and bought up their own currencies from the market. Dollar’s supply in the market will rise and its relative value (exchange rate) will fall. A cheaper dollar will allow US exporters to get back into the game.

This may sound too good to be true but it has happened in the past. In 1985, the US signed the Plaza Accord — named after the Plaza Hotel in New York that was the venue — with the other top economies of that time: Japan, Germany, France and the UK (the G-5).

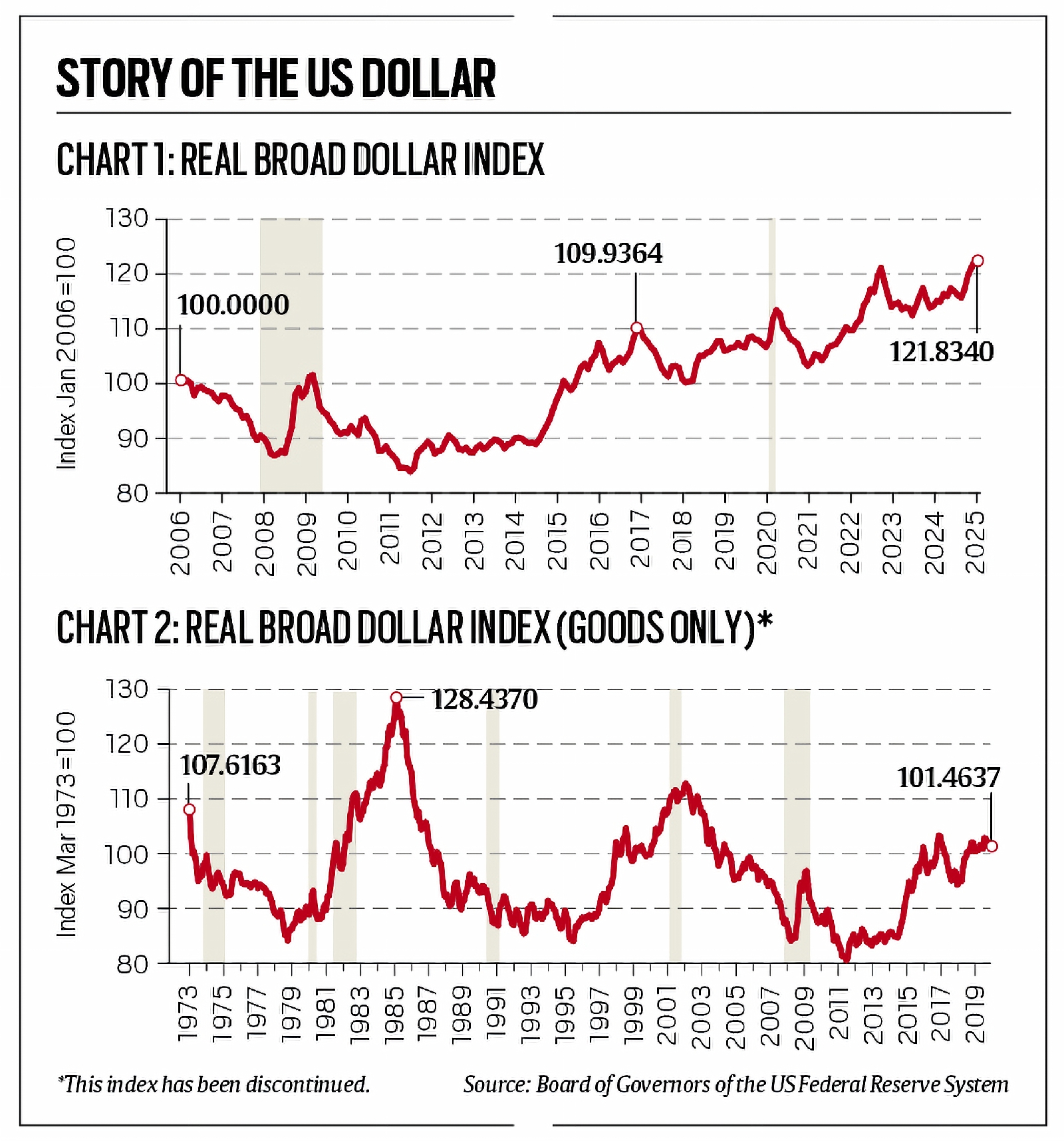

In a coordinated manner, the exchange rate of the dollar was brought down sharply. (Chart 2).

The US exchange rate is again reaching very high levels (Chart 1) and that explains the chorus for some kind of remedy.

The rumoured Mar-a-Lago Accord essentially refers to a Plaza Accord-like agreement that Trump may sign at a later stage.

Why G-5 signed the Plaza Accord

A fall in the US exchange rate meant a rise in the exchange rates of all the other currencies (German Mark, Japanese Yen, British Pound, French Franc).

These countries knew that a high exchange rate would immediately hurt their exports competitiveness but the US convinced them to accept dollar devaluation as against facing the uglier option: High tariffs — something that Trump is doing now.

The fact is that in the run up to the Plaza Accord of 1985, US dollar had strengthened to historic high, and the US Congress was on the verge of legislating deeply protectionist measures such as tariffs. That would have been bad for all concerned. So the rest of the G5 decided to swallow a bitter pill in the short term in the hope that it will allow for free flow of trade in the longer term.

Was the Plaza Accord a success?

Yes, and no. From the US perspective, they were successful to the extent that in the short to medium term they brought down the US exchange rate and relieved it of the yawning trade deficits.

But the fact that four decades later, the US is back to where it was, suggests that this is not a one-time solution.

Moreover, it did not work out so well for some of the other partners.

Japan in particular bore the brunt of it. It was an export-led economy and the spike in its exchange rate hit its exports competitiveness. In a bid to stimulate the domestic economy, Japan lowered interest rates. Between high exchange rates and a speculative boom fuelled by low interest rates, Japan saw price bubbles in different sectors of its economy such as the real estate market and the stock markets.

In the absence of commensurate growth in the real economy, these bubbles burst in a few years and from the early 1990s onwards, Japan has spent decades in economic stagnancy from which it is yet to fully recover.

Mar-a-Lago Accord: How likely?

Far more difficult than 1985.

For one, Japan’s case is a cautionary tale.

Second, unlike 1985, there are far more countries involved today. The G-5 has given way to G20.

Even more crucially, the nature of alignment has changed. In 1985, US’s trade adversaries (Germany and Japan) were its military allies. Today, its trade adversary is China, which is also its chief military adversary.

Fourth, beyond the number of countries, the monetary scale at which a readjustment is required is also humongous. A report in Bloomberg by John Authers quotes Tiffany Wilding, economist at Pimco, to suggest that the scale of interventions required for meaningful devaluation of the dollar is “staggering”

“Currency markets today see daily average turnover of some $7.5 trillion, according to the Bank for International Settlements. Even after adjusting for inflation, that’s about five times greater than the volume in 1989, in the years after the Plaza Accord,” according to Wilding.

Lastly, if Trump wanted to bring global leaders around and convince them to do something that was detrimental to their country’s economy and their own political futures, he has gone about it the wrong way.

Or, so it would seem.

It is instructive to hear the comments that Scott Bessent, US Treasury Secretary (and someone who has worked for George Soros for a long time), made in the run-up to the presidential election last year.

“Tariffs for the sake of tariffs aren’t interesting. But there is an old Soviet nuclear strategy: Escalate to de-escalate. Fortunately it has not been used so far. But I think you can put tariffs on with the idea of getting rid of all tariffs.”

Perhaps Trump is employing the Soviet dictum, and the ongoing chaos of tariffs is just the escalation he needs to get every country to agree for a devaluation of the US dollar.

Share your views and queries at udit.misra@expressindia.com

Take care,

Udit

More Explained

Must Read

EXPRESS OPINION

Mar 25: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05