Interpreting corporate reports on carbon emissions can be challenging. The current, adhoc approach to how businesses share this information makes it difficult to see whether they have set the right targets, have realistic plans to meet them or are being transparent about their progress.

While there are frameworks for reporting climate and sustainability data, there are still big differences in the way the data is being disclosed.

We developed the Climate Action Tracker Aotearoa (CATA) to address these issues. Based on the global Net Zero Tracker, CATA evaluates company reports and climate plans to share and explain their climate action.

Using the tracker, we analysed 21 companies in Aotearoa New Zealand, focusing on the top emitters and companies in the energy, retail, agriculture and transport sectors, as well as the banking sector.

We evaluated three aspects – targets, plans and reporting – by reading through publicly available information provided by the company. These three aspects help make sense of what a company is doing and going to do to mitigate climate change.

Here is what we found.

Setting targets

While the majority of companies have 2030 targets (86%) and absolute targets (81%), only five companies of the 21 (25%) have targets that have been verified by the Science-based Targets Initiative.

All but two companies include scope one (emissions the company creates directly) and scope two (emissions created indirectly from, for example electricity or energy it buys for heating and cooling buildings) – the areas companies have the most control and ownership over. But when it comes to scope three emissions, which come from company travel in planes, trains and taxis, and the supply chain, far fewer companies have set such targets.

Scope three targets are difficult to set due as they involve a large number of supply chain partners. But understanding the full impact of a company’s emissions is an important factor towards meeting the Paris Agreement targets.

Making plans

It is in the planning that there starts to be a divergence in the results across the companies. It would seem that it is easier to set a target than provide detailed plans on how to reach it.

Some companies do this very well, laying out a transparent and plausible climate map (Meridian Energy, for example). But many companies have failed to provide enough detail to be able to understand just how the reductions might occur.

It is even harder to understand how companies plan to use carbon offsets and credits.

Carbon offsetting involves a reduction or avoidance of emissions that can be used to compensate for emissions elsewhere. For example, offset projects could include renewable energy projects or energy efficiency improvements.

We found that just over half of the companies were offsetting or intending to, with only two stating they will only offset hard-to-abate emissions.

According to the University of Oxford Offsetting Principles, the best practice is to reduce as much as possible and use offsetting closer to the net zero date (2050) for those residual emissions.

It is not great to be seeing offsetting already in use.

We also found companies are not always transparent about their policy for using offsets. The majority either did not specify conditions for offsetting or just didn’t have any conditions to begin with.

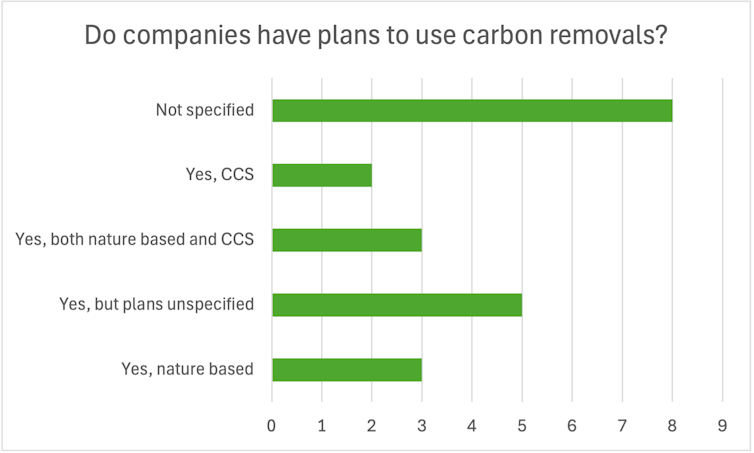

The majority of companies were unspecified in their approach to carbon removals (the process of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere).

The carbon removal measures that were mentioned were nature-based (such as planting a mixture of exotic and native trees) and carbon capture and storage (CCS). These tended to be from companies that also operated overseas.

The World Economic Forum outlined the best practice for voluntary carbon removals last year.

Carbon removals were seen as necessary for the hard to reduce emissions, to reverse the build up of historical emissions, and deal with feedback loops in natural processes such as forest fires.

In 2022, the Ministry for the Environment also published a set of principles around carbon removals. These principles included that information needs to be transparent, clearly stated and publicly available.

We found the minority of companies adhered to such standards. Therefore, more transparency is needed on both offsetting and removals in their reporting.

Reporting climate action

The majority of companies are reporting carbon emissions and providing some level of detail on the emissions to an international standard.

But at the same time, many companies are making it very difficult to find and piece together the data needed to clearly see what climate action they are undertaking.

We know that voluntary disclosing on social and environmental impacts can be a result of pressure from stakeholders. But it can also be used as a way to conform to these societal expectations without giving sufficient information.

Throughout our research, we found a mixture of conformity and diversion. Some companies provided vast amounts of positive information about some of their impacts, some provided multiple reports with information scattered between them, and then some were straightforward with the required information.

Companies should use CATA as a tool to benchmark themselves and their reporting to be able to provide a sufficient and transparent level of information to stakeholders, partners, investors and consumers.

This will allow consistency across industry, the implementation of science-based targets, the development of detailed action plans and easy access to comprehensive, clear and concise reports.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of their fellow researchers on this project: Lucy Mitchell, Pii-Tuulia Nikula and Limi Prestwood-Smith.