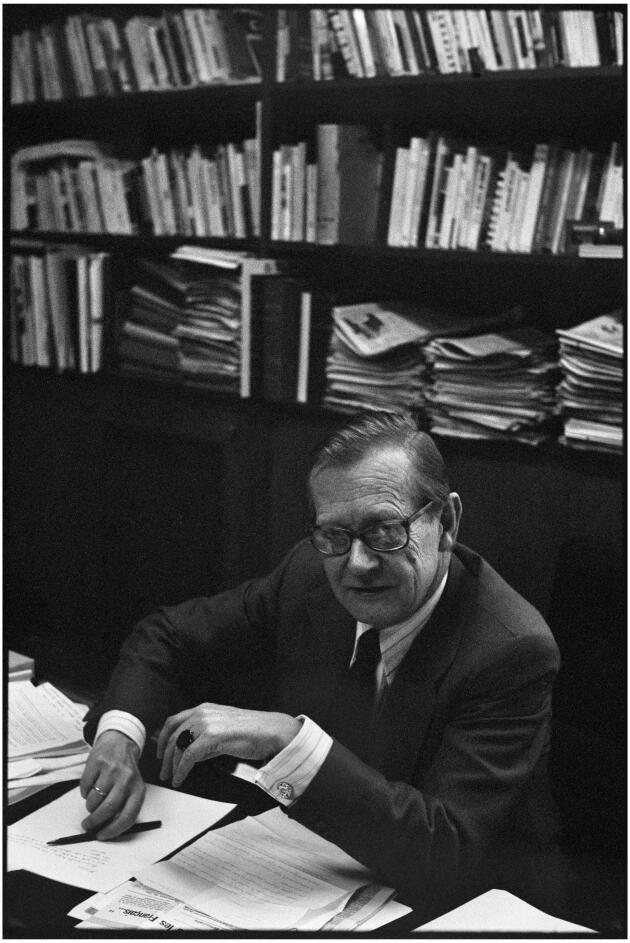

On September 18, 1958, Le Monde's founder Hubert Beuve-Méry had an appointment with General Charles de Gaulle – something remarkable, given that the two men had been carefully keeping their distance since the Liberation, 14 years earlier. Moreover, the "boss," as Beuve-Méry was known at the newspaper, rarely rubbed shoulders with politicians. He had little interest in dinners where the gossip of the times was gleaned, and didn't seek out the company of celebrities or the powerful. Not even this general whose return to power earlier that year and whose new constitution establishing the Fifth Republic he had just endorsed, against the advice of part of the newsroom.

At the newspaper's offices, which Beuve-Méry called home, it wasn't unusual to hear him sarcastically mimic the General's throaty voice and roguish wording at the daily news conference held in the morning in his office. But Beuve-Méry, a Christian democrat, liked to say: "I've never been a Gaullist, even during the war, if by Gaullist we mean this total adhesion to a person." Under his leadership, Le Monde supported Pierre Mendès France, a left-wing prime minister for eight months in 1954-55, and his policy of decolonization in Indochina (present-day Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam), Morocco and Tunisia. Beuve-Méry, a Jansenist, had no taste for political parties, and was particularly wary of de Gaulle's, the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF), which refused to accept the right-left divide, even though it leaned towards the right, arousing the journalist's suspicion. What's more, the obsessive independent had an ambivalent relationship with the war hero who had made him director of the "newspaper of reference."

That fact, even though it was left unsaid, hung heavily over the two men's meeting in 1958. Between the future president who often said "I, General de Gaulle" and "France" as if the two were one and the same, and the director of Le Monde whose pseudonym when signing his editorials was Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, it was more than a battle between two proud individuals. There was an initial ambiguity. Once, de Gaulle, exasperated by critical editorials, summed up their opposition in a single sentence: "You see, Beuve-Méry doesn't forgive me for having given him Le Monde at the Liberation."

Let's pause here for a moment. Surprising as it may seem, the 1958 meeting was in fact the second between de Gaulle and Beuve-Méry. The first took place 14 years earlier, a month after the birth of Le Monde, on December 18, 1944. Beuve-Méry himself later recounted the story of this meeting between the two men from different backgrounds, born 12 years apart.

De Gaulle, first: 1.96 meters tall, still strapped into his uniform, belted at the waist. Born in 1890, he was a son of the upper middle class, a military man of course, brought up in the cult of France's greatness, and made a hero by his declaration on June 18, 1940, which made him the embodiment of the country's Resistance. In the defeat of 1940, he saw not only the collapse of the army, but also the key role that disinformation and propaganda played in the moral collapse of France and the victory of totalitarianism, which sowed war and destruction across Europe. Immediately after the war, as head of the provisional government of the French Republic, he and this new generation born of the Resistance wanted to re-establish a serious newspaper that reported on political events in France and abroad, and supported democracy, progress and a Europe in need of rebuilding. A major daily that would take the role, offices, and printing facilities of Le Temps, the Third Republic's liberal newspaper, which had discredited itself by collaborating during the Occupation.

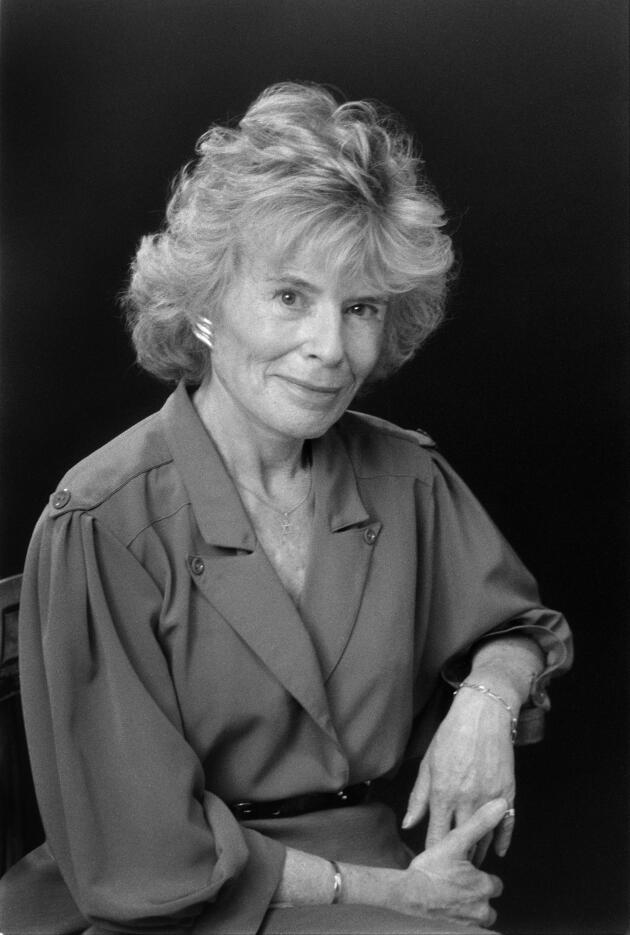

Now Beuve-Méry. At 1.80 meters, he too was quite tall for his time. Above all, he was austere and stiff. "Graceful as a cactus," later wrote the founder of L'Express Françoise Giroud, who knew how to paint a picture with just a couple of words. "He was a very hard worker, his honesty was bordering on obsession and he held it up as a banner," said his biographer, the historian Jean-Noël Jeanneney, who met him on several occasions. His only touch of elegance was a fur-lined jacket that he wore in the winter over his dark suit – just like the one worn by Jean-Pierre Cassel in L'Armée des ombres (1969, Army of Shadows), Jean-Pierre Melville's masterpiece on the Resistance. Born in 1902, the son of a seamstress and a watchmaker-jeweler whose first name was also Hubert and who died when his son was 6, "Beuve," as he was known, had a modest childhood, but studied literature and law. A Catholic journalist, he started out at Nouvelles religieuses ("Religious News") before becoming a correspondent for Le Temps in Prague. From there, he resigned in 1938 to protest against the abandonment of Czechoslovakia during the Munich Agreement, and the following year warned of the threat posed by Adolf Hitler in an anxious but clear-sighted book entitled Vers la plus grande Allemagne ("Toward a Greater Germany").

De Gaulle was well aware that Beuve-Méry came to the Resistance late. "You weren't one of mine," he once told him. In 1940, Beuve-Méry did not go to London, but believed in the possibility of Philippe Pétain being a "shield." Beuve-Méry attended the Ecole d'Uriage, which was supposed to provide top civil servants to the Vichy regime. Resolutely opposed to Nazism, in 1942 he broke with Vichy to join the Maquis resistance bands.

Beuve was well aware that it was not de Gaulle who chose him to run Le Monde, but rather Pierre-Henri Teitgen, a journalist's son and, above all, the boss of the Christian democratic party Mouvement Républicain Populaire (MRP). "I had resigned from Le Temps at the time of Munich, I had just come back from the maquis, in short, a combination of circumstances made me appear as the ideal person," Beuve-Méry later wrote. Curiously, during the first meeting between the journalist and de Gaulle, Beuve-Méry suggested meeting weekly with the government's information officers, "fearing that I would be insufficiently informed in such troubled times," he later explained. De Gaulle retorted imperiously: "Bah, they're civil servants, you'll manage on your own."

Beuve-Méry did indeed "manage." Le Monde, with its tightly-written articles, balanced headlines, austere photo-less printing, and well-known writers, became the newspaper of the French intelligentsia, and an intractable counter-power, as well. And that was exactly what annoyed de Gaulle. The General didn't like journalists. Journalists rarely like generals. But Le Monde, with its 250,000 copies sold, became indispensable.

'I read it and I'm very amused'

In 1958, for de Gaulle to agree to meet with Beuve-Méry, it took all the interpersonal skills of Pierre Viansson-Ponté, the new head of the politics desk. Jacques Fauvet, who had previously reigned over that department, had just been appointed deputy editor-in-chief. The subtle Viansson-Ponté had been poached from L'Express four months earlier and arrived at Le Monde on May 12, 1958, the day before the Algiers coup that would precipitate de Gaulle's return to power. After that, he watched in awe as the daily newspaper's inner workings were shaken up. When Beuve-Méry, aka Sirius, wrote in his editorial that de Gaulle's return was a "lesser evil," then called for a "yes" vote on the Constitution of the Fifth Republic, he was met with a rebellion from several journalists at the politics desk. This was the tradition at Le Monde: free debates, and, given that the journalists' association was a shareholder in the newspaper, while they addressed the "boss" with respect, they could also contradict him. The rebels at the politics desk obtained permission for the newspaper to publish a short text stating that they could not "be represented by positions taken without them, at particularly serious times for a regime to which they remain attached."

Viansson-Ponté was more centrist and less opposed to de Gaulle than the journalists in his department. In the early days of his career, between a position at Agence France-Presse (AFP) and the founding of L'Express, in 1952, he served for 40 days as an adviser to Edgar Faure, a short-lived prime minister. His moving back and forth between politics and journalism hadn't shocked anyone. As a keen political observer, he understood that the Fourth Republic, with its 22 governments in 12 years, was dead and buried. He also correctly guessed the distance between Beuve-Méry and the General. He was a moderate who "loved politics like others love theater." While he considered it unwise to make Le Monde a pro-government newspaper, he thought it was a good thing for the "boss" and the president to at least talk to each other.

Given that this subtle writer, who was a lover of literature and something of a socialite, regularly dined at the home of future president Georges Pompidou on Paris's Ile Saint-Louis, all he had to do was call the former Rothschilds banker, who had for a time been de Gaulle's chief of staff, to organize the meeting at the Elysée between Beuve-Méry and the General.

"Ah, Le Monde... I see the talent, the success, the circulation. It is read. I read it and I'm very amused. You know so many things... Newspapers are very entertaining..." de Gaulle began, mockingly. "General, that's not exactly our aim in making this newspaper, with all the difficulties that you are well aware of. But after all, the kings of France had their jesters who sometimes did them favors while amusing them..." retorted the journalist, defending his vision of Le Monde as a counterpower.

This was just the start of a long joust that lasted 11 years, until De Gaulle left the Elysée in 1969. Le Monde's journalists investigated and denounced torture in Algeria and then wrote about decolonization (the newspaper has always been anti-colonialist), the political rivalries between the president and his prime minister, the "Françafrique" system of relations put in place by de Gaulle's adviser Jacques Foccart, and the shady actions of the Civil Action Service (SAC), which acted as a parallel police force for the president. Did Beuve-Méry know that Prime Minister Michel Debré had him wiretapped?

'What a thistle in my pants!'

In his editorials, Sirius set out the values of a democratic, progressive and European newspaper. He has also established a tradition whereby the newspaper publicly took position, before a presidential election or referendum, believing that Le Monde owed its readers such transparency. In 1958, for example, he gave a "conditional and provisional yes" to the return to power of the General. In 1962, he called for a no vote in the referendum that would establish the election of the president by direct universal suffrage, replacing an electoral college, out of fear that it would reinforce "the prince's pleasure." The yes vote prevailed, but Sirius spoiled the Gaullist victory with one sentence: "Enough votes for a referendum, too few for a plebiscite." The General retorted in his own way: "That Beuve-Méry, what a thistle in my pants!" He always refused to be photographed while reading such an infuriating newspaper.

The General's non-Atlantist policy should have pleased Beuve-Méry, who was suspicious of the overly capitalist United States. But here again, the paper's director was critical, in his desire to be fundamentally independent of the government. In 1965, he spoke out against the president's re-election. In 1968, when the paper was printing 800,000 copies during the May riots, he wondered aloud about the leader's age and his "omnipresent self." De Gaulle, exasperated by these criticisms, ended up nicknaming the daily "L'immonde" ("The Foul") and Beuve-Méry "Mr. It-has-to-fail."

Sometimes, when two worthy opponents meet, they end up leaving the stage at the same. In 1969, Sirius called for a no vote ahead of the referendum organized by the president after the May '68 crisis. The no won, provoking de Gaulle's resignation. And Beuve-Méry followed suit six months later. The youngest member of the editorial staff, 23-year-old Robert Solé, handed him the keys to a little DAF, a Dutch car with a Renault engine, gifted by the journalists. He was able to drive from his Paris home to the outskirts of Fontainebleau, where he had a house. Although he had left his position as director of the newspapers to Jacques Fauvet, Beuve-Méry kept an office on the fifth floor of the building on the Rue des Italiens, in the 9th arrondissement of the capital. From there, he watched over the newspaper, like a commander's statue.

The generation that had lived through the war was still running the paper, but Fauvet, 12 years Beuve's junior, was more left-wing than him. He had been a prisoner of war for five years in an Oflag, 50 kilometers from Dresden, Germany, and retained a form of respect for the Red Army, which had liberated him. He may not have been a communist, but he was not afraid of the left uniting.

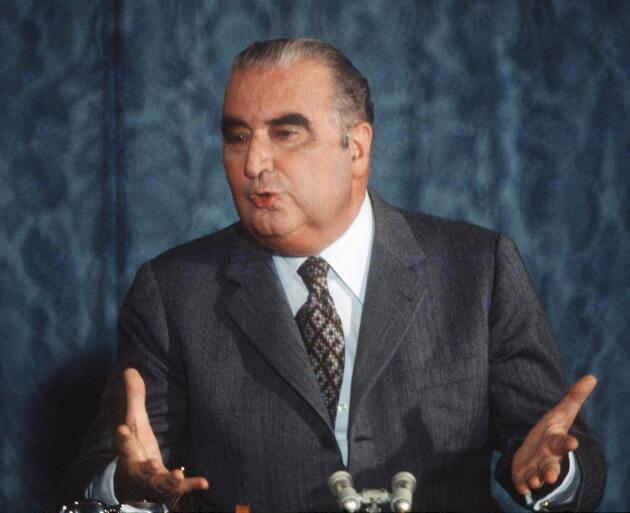

Silence surrounding Pompidou's illness

It would be many years still until the Socialists and Communists clinched their joint victory. For the time being, the new president, Georges Pompidou, may have had a taste for modernity, but the Gaullist right was still in power. Le Monde's politics desk has expanded. The old hands of parliamentary politics still reigned supreme, including Raymond Barrillon, whom Fauvet had put in charge of the department to keep his rival Viansson-Ponté at bay. But Viansson-Ponté, who was allowed to write a weekly column, introduced finely chiseled political portraits, genre scenes, and, in short, a touch of human psychology that gave soul to the chronicles of power.

When did he realize that Pompidou was ill? Did he discuss this with his colleague Claudine Escoffier-Lambiotte, a doctor who had gotten Beuve-Méry to agree on the creation of the medical section in 1967? The famed professor Jean Bernard, who knew them both, would confirm years later that Pompidou himself knew even before his election that he was suffering from a rare bone marrow disorder. The seriousness of Waldenström's disease, which causes headaches, nosebleeds and frequent bouts of flu, was well known to Pompidou's own son Alain, who was also a doctor, and was in fact more familiar with its seriousness than his father, he would later recount.

The newspaper, for its part, only mentioned Pompidou's health with the utmost precautions. Le Monde still viewed the subject as a matter of private life. In 1964, General de Gaulle's prostate operation had been reported by AFP and picked by Le Monde only because the General had allowed it. This time, Pompidou's visible weakness remained a taboo at the Elysée itself, and the newspaper settled for short news items evoking the president's recurring bouts of "flu." Only the quotation marks instilled doubts about the seriousness of the ailment.

On June 3, 1973, however, Pompidou's cortisone-swollen face was a shock to all viewers following his rare travels on television. That time, Viansson-Ponté wrote frankly in his weekly column: "As soon as it upsets events, changes behavior, leads to actions or refusals, ultimately has an impact on propaganda, changes in opinion, demonstrations, or even strikes, the president's health, whether excellent or mediocre, is no longer his property, his problem or his concern, but ours." He returned to the topic several times, including on April 7, 1974, five days after Pompidou's death, when he deplored the fact that the French had been lied to to the end about the president's health, saying they had been treated as a "nation of children, who can be offered naïve images to amuse them, but who have no right to the truth."

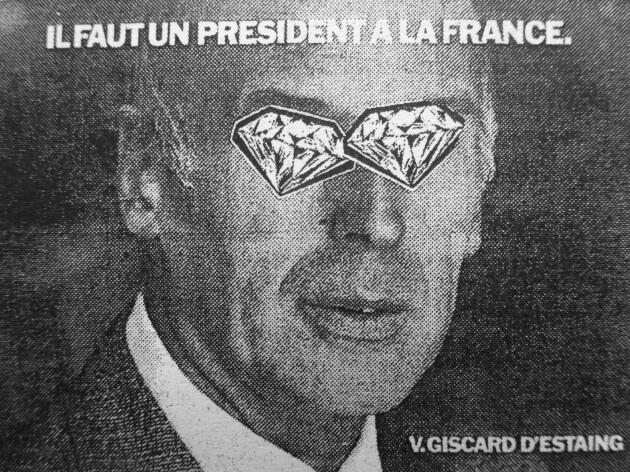

A month later, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing was elected over François Mitterrand by a narrow margin, with 50.66% of the vote. On the front page, Fauvet wrote: "This time, the country has been cut in two. (...) Even if the right dominates its success and the left its disappointment, the split is there: between generations, regions, and social categories, not to say classes."

Giscard kept Le Monde at bay

Le Monde did not dislike the new government's first reforms. It supported the lowering of the age of majority to 18, the legalization of abortion, the break-up of the ORTF radio and television agency, and the authorization of divorce by mutual consent. But after less than six months, the president's popularity was plummeting, and Thomas Ferenczi penned a lengthy front-page article entitled "A certain 'solitary exercise of power.'"

Ferenczi, who was covering the Elysée at the time, underlined the distant, monarchical nature of the president, behind his modern appearance. He also noted the jealously guarded secrecy surrounding the private life of a president who easily disappeared for entire weekends "without his aides knowing where he was." The article displeased "VGE" so much that the young president excluded Ferenczi from all his invitations to the Elysée, when he would talk off the record with journalists over tea. When the two did meet, he was now "so distant that it was impossible to have the slightest conversation with him."

When Noël-Jean Bergeroux replaced Ferenczi, the relationship did not improve. "Bergeroux, is that a name from the Massif Central?" asked Giscard when they first met. "Yes, from the Puy-de-Dôme." "I would have bet it was from the Cantal." The conversation went no further. But there was much to investigate about this president, whose vision for the 1970s faded so quickly to give way to mannerisms reminiscent of the Ancien Régime.

It has to be said that the newspaper seemed to be much more inclined toward the left. Giscard d'Estaing was well aware that Barrillon, now the head of the politics department, had been a long-time believer in Mendès France, liked to play table tennis with Mitterrand, and remained hopeful that a united left would soon come to power. Thierry Pfister, who was covering the Socialists, was a former student union leader who made no secret of his closeness to Pierre Mauroy, the left's future prime minister, whom he would join as an adviser in 1981. Worse still, in the eyes of the president, the only man from the right who seemed to find favor in Le Monde was his main rival, Jacques Chirac, whose growing ambition was regularly covered by André Passeron. The reported pitched articles on the "relaunch of the Chirac project" with such regularity that it would make his colleagues smile.

The paper's economy desk was much more divided. There were experts in macroeconomics, such as Alain Vernholes, who dissected the state budget every year. And while Gilbert Mathieu, a tall, jovial fellow, was an avowed supporter of the Socialists, Paul Fabra, a specialist in monetary issues, seemed frankly skeptical about the economic slogans and promises of the alliance between Socialists, Communists and Radicals.

Mutual exasperation

At first, the French president tried to soften Fauvet by offering him a Legion of Honor, but to no avail. Every time the president and the director of Le Monde met, they both came away exasperated. Giscard d'Estaing addressed most journalists with haughty contempt, and Fauvet hated the way he explained his politics, like a teacher lecturing to students too mediocre to understand the material. Fauvet had also hired a new editorialist, whose sharp writing was like an additional weapon against the Elysée.

With his moustache, colorful scarves and dandylike appearance, Philippe Boucher always seemed to hesitate between sarcasm and severity when it came to writing about Giscard. Within the editorial team, his witticisms were a source of laughter at the morning conference, and his favorite target was the president, whose whispered way of speaking he imitated. Always on the lookout for information that would shake up the newspaper's balanced, eloquent, and traditional wisdom, he called for more vigorous investigations and often railed against the "freedom-destroying" laws of Interior Minister Michel Poniatowski and Justice Minister Alain Peyrefitte. Above all, the openly gay man had an unprecedented influence in a newsroom where Beuve-Méry had stated not that long ago: "You don't give responsibilities to men like that." Fauvet, though, first appointed him as head of the society desk, before offering him a unique position in the newspaper: editorialist reporting to the director.

In this little fortress, on October 9, 1979, Boucher read the edition of the satyrical and investigative newspaper Le Canard enchaîné due to appear in kiosks the following day. The weekly was publishing a fax of an order placed by Central African Republic's leader Jean Bedel Bokassa, who had crowned himself emperor in 1977, and had been overthrown a month earlier. In the document, dated from 1973, Bokassa ordered a 30-carat diamond plate, destined for France's then finance and economy minister: Giscard d'Estaing. The day after Bokassa's fall, in September 1979, Le Monde had published an opinion piece by a former French ambassador to the Central African Republic, which detailed the gifts that Bokassa would bestow on his official visitors in his heyday. It seemed plausible that, thanks to the change of regime and the disarray of the Central African administration, Le Canard had indeed gotten its hands on proof of this "gift" that was proving quite embarrassing for the French president.

The diamond bomb

Usually, Le Monde would never reprint a claim without verifying it, and Barrillon, the head of the politics desk, put the brakes on. But Boucher took it upon himself to "cobble together" an unsigned double-page spread. By putting together the Canard scoop on Bokassa's diamonds, a dormant article on investments by two of Giscard d'Estaing's cousins in Chad and Cameroon, a piece on the practice of gift-giving in France and abroad, a brief update on the situation in the Central African Republic, a short history of accusations made against French presidents since the Third Republic, including the "nugget" once offered to de Gaulle but left behind at the French embassy in Brazzaville by the General who was "exceptionally fussy on the subject," and an article based on reports from the far-right weekly Minute on the building permit obtained by Prime Minister Raymond Barre in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, there was enough, Boucher said, to slap the topic on the front page.

On October 10, 1979, the two-page spread was a bombshell. If the newspaper of reference was picking up Le Canard enchaîné's scoop, it must be true. Armed with Le Monde's legitimacy, AFP asked the Elysée to respond. The politics desk was unsure how to proceed. "Many of us were discomforted to see this story come out a year and a half before the presidential election," remembered André Laurens, who was then the deputy head of the department. "Some even considered the affair minor and, in any case, the politics desk wouldn't admit that this manhunt against Giscard had gotten out of hand."

Furious, the president refused to read the evening paper. He blurted out to Le Monde's Elysée reporter, Bergeroux, "I'm not angry with you personally, but if I'm re-elected, the paper won't be getting any presents." He was not re-elected. On May 10, 1981, Mitterrand won the presidential election. Shortly after 8 pm, Fauvet went up to the second floor to congratulate Barrillon, and the other journalists watched in amazement as the two wept in each other's arms.

Ten days later, an unsigned vitriolic editorial, on the front page, in fact written by Boucher, violently denounced Giscard's behavior: "This mascarade may not have been odious, but it was grotesque! The grotesqueness of it all has fallen on the whole of France," he wrote. "Nowadays, it is fitting that the new president should choose to visit the republican Panthéon and refer to Jean Jaurès, rather than dreaming of Louis XV!'" (On the day of his inauguration, Mitterrand visited the Panthéon to lay a rose before the tombs of left-wing and pacifist leader Jean Jaurès, abolitionist Victor Schoelcher, and resistant Jean Moulin.)

This time, the association of Le Monde's journalists took up the matter. The result was that moving forward, editorials were to be carefully reread to prevent any "slippage that would call into question the spirit of criticism and objection to the powers that be." Fauvet left two years later, soon to be appointed by Mitterrand as president of the National Commission on Computer Science and Freedom.

Le Monde's readers didn't like it much that their newspaper was abandoning its role as a rigorous, distanced source of information. The economy desk was still quick to describe the Socialists' difficulties – one journalist, Alain Vernholes, who kept his own statistics, warned Jean-Yves Lhomeau, who was then following the left at the politics desk, that "the government is heading for a wall" because of its nationalizations and deficit-deepening wage increases. But the editorials were too enthusiastic about the left's first steps in power. In 1983, the daily suffered the disillusionment that accompanies such beginnings, and its sales declined dangerously. In 1983 alone, circulation dropped from 400,000 to 300,000 copies. The new director, André Laurens, who had succeeded Fauvet in 1982, was elected by the journalists, as had been the custom since 1951, on the grounds that Le Monde had shown itself to be too partisan and had jeopardized its identity. At that point, the daily resumed its role as a counter-power, publishing harsh economic and political investigations of this Socialist president who so quickly became entrenched in the institutions of the Fifth Republic.

Mitterrand's counter-attack

The counter-attack did not wait long. It came at the end of 1984, after the publication of an impertinent but seemingly innocuous article by Claude Sarraute. The piquant journalist published a short droll column every day, in the top right-hand corner of the newspaper's back page, and it quickly became a very popular fixture. The visit of Gabon's President Omar Bongo was a perfect occasion for mocking the French president, whom she nicknamed "my Mimi," as if he were a buddy at the bistro: "Bongo can't complain, we've spoiled him, there's no denying it. (...) All those ministers gathered at the foot of the stairs behind the president of the Republic. (...) And Mitterrand looking more and more imperial (...) with his Roman emperor mask. My friends and I only call him Mittolini now."

"Mittolini," as if she was saying Mussolini! Mitterrand hated the fact that this impertinent woman, wife of the essayist Jean-François Revel – who never missed an opportunity to vilify him in the magazine Le Point – made an allusion to his health when describing his waxy complexion and, even worse, to his private life. "Bongo's no fool," wrote Sarraute. "He's well aware that, when it comes to preserving his private life, Mitterrand is much less serene. Much less broad-minded. He looks for and finds ways to prevent the publication of newspapers and books that could topple him from his pedestal."

When it came to the president's health, no one at Le Monde saw any malice. When he was elected, the newspaper's medical specialist, Escoffier-Lambiotte – who was there already under Pompidou – told the editor-in-chief the rumor going around about the president: "He's ill." However, after seeing him carry out his duties with no apparent difficulty, the newspaper eventually "forgot" about the alert. Regarding his private life, until Sarraute's column, Le Monde had never made the slightest allusion to Mazarine, the secret daughter Mitterrand had with museum curator Anne Pingeot. Rumors did spread, however. A few months earlier, Jean-Yves Lhomeau and a number of his colleagues had met the president for breakfast at the Elysée Palace. When TF1 journalist Claude Sérillon dared to ask the president, "Rumor has it you have a daughter, Mr. President...," Mitterrand replied, "Yes, so what?" All the newsrooms, including Le Monde, left it at that. They ignored the fact that, to preserve his secret, Mitterrand assigned François de Grossouvre to play the "minister of private life," as he was known at the Elysée. They were completely unaware that the president had had the far-right newspaper Minute and the novelist Jean-Edern Hallier, who was planning to write a book about Mazarine, surveilled and wiretapped.

Pressure from the Elysée

The newspaper's director would not survive this allusion to the president's private life. While Laurens needed the support of the BNP bank, René Thomas, who had been chosen by Mitterrand two years earlier to head the newly nationalized establishment, refused his austerity plan. Thomas, who was close to Mitterrand's brother Jacques Mitterrand, was also the future husband of Laurence Soudet, a presidential aide who looked after Mazarine and her mother. "The salaries won't be paid, unless you promise me that Laurens is leaving," asserted Thomas at the end of 1984, to the representatives of the journalists' association, which, as a shareholder, had come to plead the newspaper's cause. In 1985, André Fontaine was elected director of Le Monde. Fontaine, who had the manners of a diplomat, came from the foreign desk, and it was the first time since Beuve-Méry that the paper's director was not from the politics desk.

Mitterrand thought he'd brought Le Monde into line. He was soon to be disappointed. Sitting in a small office, police reporter Edwy Plenel seemed on the lookout for anything that might feed his investigations and turn them into scoops. With his jet-black mustache, dark shirts and those little cigars he liked to smoke as he typed his articles, he had the fierce style of a Chilean revolutionary and a taste for state secrets. Four years before joining Le Monde, in 1980, he had covered education and higher education for Rouge, a communist magazine. Thanks to his contacts among the police and the Interior Ministry, he enjoyed a formidable network of informers. The essence of his American-style investigations was to measure up to the powerful and to uncover state scandals.

As early as January 1985, he denounced the actions of the Elysée's anti-terrorist cell in the so-called "Irish of Vincennes" scandal, leading the investigation in concert with a journalist from Le Canard enchaîné, Georges Marion, who was also a former Rouge employee and would soon join Le Monde. A few months later, on July 10, 1985, two explosions partially destroyed the hull of the Rainbow Warrior, a Greenpeace ship anchored in Auckland, New Zealand, killing Fernando Pereira, the environmentalist NGO's photographer. In Le Monde, the news was only mentioned in a short filler. The ship had been due to set sail to interfere with French nuclear testing on the Mururoa atoll, but Greenpeace was still a small environmentalist organization with no real influence. It wasn't until August that two journalists, Pascal Krop, at L'Evénement du jeudi, and Jacques-Marie Bourget, at VSD, revealed that the French secret services were behind the attack, after New Zealand authorities arrested two French agents.

On Rue des Italiens, Plenel, 32 set about his investigation. At first, he erred a bit, writing that the attack had been incited by the far right, but this was untrue and he was forced to make amends. Nonetheless, he persevered with the investigation, recounting how France's foreign intelligence agency, the DGSE, infiltrated Greenpeace. Plenel and his colleague Bertrand Le Gendre revealed the existence of a third team.

Independence and de-ideologization

Fontaine quickly realized that Le Monde could only restore its image and win back its readers by asserting its independence from presidential power. He supported his investigators, but feared they could make an error that would bring the paper into disrepute and, perhaps, result in a counter-attack from the government. So he spread the scoop over four columns on the front page, but wrote a headline that allowed for some uncertainty: "The Rainbow Warrior may have been sunk by a third team of French soldiers." Then he called Mitterrand's chief of staff, Jean-Louis Bianco, to give him a head's up, but took care to add: "The presses are running." There would be no stopping the news in its tracks.

Plenel knew how to put forward his investigations. He alerted the rest of the press to the publishing of his revelations, in order to better amplify their impact. At the Elysée, the battle was on: The president had to be protected, and Le Monde and "this Trotskyist who wanted to bring down social democracy" had to be discredited. Mitterrand was relieved when Prime Minister Laurent Fabius, who was not involved in the operation, forced Defense Minister Charles Hernu to resign on September 20. The head of the politics desk, Jean-Marie Colombani, was so delighted that he invited the investigators and journalists from his department, who had worked together on the Greenpeace scandal and its consequences, for drinks.

Colombani and Plenel couldn't have been more different. The former was a Christian Democrat like Beuve-Méry, a centrist with a love of politics and an implacable sense of the rules of loyalty. This was "his Corsican side," as was said at the paper. Since taking over as head of the politics desk, he continued to "de-ideologize" it, so that the paper "was no longer a companion of the left," he said recently. Plenel remained what he himself calls a "cultural Trotskyist." Both understood that Le Monde's audience and influence could only grow by making the daily an intractable counterweight. Their alliance was a war machine. After many twists and turns, they eventually took control of the newsroom in 1994. With Colombani at as director, the politics desk returned to power. "Politics is the newspaper's DNA," he said. "If the paper moves away from it, it declines." But at the time, Plenel, Le Monde's most emblematic investigator, took over as editor-in-chief, and this pairing reflected the changes in a society whose elected representatives were increasingly challenged publicly. Sales of Le Monde climbed at a steady pace.

It was the end of Mitterrand's reign. Not a month, sometimes a week, went by without the press in general, and Le Monde in particular, unraveling the hidden twists and turns of this character who seems like he could've come from a novel: his actions during World War II (he was suspected of having collaborated), his hidden daughter, his corrupt friends, his cancer. In 1995, at the end of his second term, there was almost no doubt that after 14 years of Socialist rule, the right would win the presidential election, having already won the parliamentary elections in 1993, which had forced Mitterrand to appoint a right-wing prime minister. "Every time the prime minister shakes my hand, I feel like he's taking my pulse," sighed Mitterrand, referring to Edouard Balladur, who was no longer hiding his presidential ambitions.

Colombani had never concealed his contempt for Chirac, Balladur's rival from within the same party, who was also running for president. As the head of Le Monde's advisory board, Alain Minc, an essayist and adviser to the powerful, had no editorial role, but was seen constantly in the newspaper's corridors. It was clear that his preference was also Balladur, more outspokenly European, liberal and classically conservative, rather than Chirac. "Balladur was the circle of reason," Minc summed up. The newspaper's front page also featured analyses by pollster Jérôme Jaffré, predicting an inevitable victory for Balladur in the presidential election. "Trotsko-Balladurism" is how Jean-François Kahn, director of the magazine L'Evénement du jeudi, sardonically described Le Monde's editorial line under the leadership of Plenel and Colombani.

Chirac's notes

But Chirac won the presidential election. And Le Monde's journalists soon realized that this man who had led so many campaigns, right up to the last one in which he had to beat his rival Balladur from within his own camp, didn't know what to do with power. "Content with little," is how Colombani titled his editorial on July 18, 1995. Two years later, Chirac found himself left with very little power, after calling early parliamentary elections in 1997 which yielded a left-wing majority. Power suddenly shifted to the prime minister's office, as Lionel Jospin, a Socialist, took over as head of government. Coverage of the Elysée became the story of a president with no power.

Le Monde's politics desk, under the direction of Patrick Jarreau, witnessed the arrival of a new generation born into journalism with the fall of the Berlin Wall. They were wary of ideologies, had grasped the extent to which Europe and globalization had weakened national sovereignty, and were keen to decipher the effects of communication, as these political marketing techniques are called, which had never been more powerful, now that the reality of power was waning. Chirac, for his part, seemed incapable of speaking directly to journalists, and when he met with half a dozen of them at the Elysée, he dutifully read them the notes written for him on a card, demanding to be off the record. Relations with Le Monde, which unkindly wrote about this powerless president and the corruption scandals that were surfacing, were atrocious. When he encountered the journalist who was covering him (myself), he never failed to remark: "If I said you were a good-for-nothing, you'd attack me. But I can't say anything!"

As the population grew weary of both the right and the left, the far right was making quiet progress. At Le Monde, coverage of the far-right Front National (now the Rassemblement National) had become a regular feature in 1983, when Jean-Pierre Stirbois, Jean-Marie Le Pen's lieutenant, made a spectacular breakthrough in local elections. After that, the newspaper began investigating the party, its leader, whose influence was growing, and his family. On April 18, three days before the first round of the 2002 presidential election, when the reporters following Chirac's and Jospin's campaigns had been noting for several weeks the lack of enthusiasm at rallies, the weak mobilization of the right, and the fragmentation of the left, Le Monde printed this premonitory question on its front page: "The far right in the second round?" Inside the paper, there was an investigation into "How Jean-Marie Le Pen is organizing the battle for the second round," with another angle on Chirac supporters who, facing the danger of the FN, were reassuring themselves as best they could: "What's new, in this case, is the symmetry of the handicaps against Chirac and Jospin. We have Le Pen, and they have Laguiller." (Arlette Laguiller, a six-time Trostkyist presidential candidate, obtained her best result in 2002 with 5.7% of the vote.)

Ahead of the second-round duel between Chirac and Le Pen, Le Monde called for the first time to vote for a candidate from the right – aside from Beuve-Méry's "conditional and provisional yes" to de Gaulle in 1958. Chirac was re-elected with 82.2% of the far-right challenger. Except for his 2003 refusal to engage France alongside the US in a war in Iraq, the newspaper rarely applauded the president. Indeed, he was weakened again in 2005, this time by a stroke. A double-page spread by Béatrice Gurrey, who was following Chirac's second term, was titled: "The Absentee." In it, she painstakingly described a deserted Elysée and a president who, when he traveled, seemed to be elsewhere, looking at his cards even when it was just time to say hello to those he was meeting with. "After that, I was taken off the list of accredited guests for a trip to Saint Petersburg, where Chirac was due to meet his 'friend' Putin," Gurrey remembered. Nicolas Sarkozy was already anxiously waiting at the door of the Elysée.

Plenel left Le Monde in 2004, Colombani left in 2007. For the first time, the director of Le Monde was not from the politics or international desk: Eric Fottorino had been head of the editors-at-large department for a long time, and had created the environment desk.

Sarkozy, so near, yet so far

Fottorino was also a novelist. Was that why he encouraged writing in new ways? Philippe Ridet, who was covering Sarkozy, allowed himself to tell the story of a Sarkozy in which he projected himself. "My Life with Sarko," he wrote during the 2007 presidential campaign, narrating the life of a journalist embedded in the right-wing candidate's caravan. He continued to tell the story of what he called a "generational alter ego that everything distanced from me." Portrayed alternately as a comedic or threatening character, as someone who knew all Johnny Hallyday's songs by heart but had to confront with the 2008 financial crisis, Nicolas Sarkozy sometimes balked.

In May 2009, however, an editorial by Fottorino criticizing the head of state for his "boasting and frenzy" provoked a more serious crisis. Vincent Bolloré, a friend of Sarkozy, announced that he would stop printing his free daily Direct Matin on Le Monde's presses. Le Journal du dimanche, a newspaper owned by Arnaud Lagardère, another friend of the president, also changed its printing plant. It would soon be followed by Les Echos, owned by LVMH boss Bernard Arnault, yet another friend of Sarkozy. "The powerful were trying to asphyxiate us through industrial means," said Fottorino.

The financial situation had become dire for the newspaper, which had to turn to outside shareholders: Pierre Bergé, Xavier Niel and Mathieu Pigasse. Fottorino left, soon to be replaced by a former economy reporter, Erik Izraelewicz. In 2012, when the journalists' association convened an editorial board meeting to decide on Le Monde's position in the next presidential election, a significant number of journalists insisted that the newspaper should not endorse a candidate. It was the first time such reluctance was expressed, as the second round pitted Socialist François Hollande against incumbent president Nicolas Sarkozy. "Readers no longer need to be told who to vote for," argued deputy editor-in-chief, Didier Pourquery, while editorialist Gérard Courtois stated: "We write editorials every day to say what we think about the way the world is going, but we wouldn't say what our inclination is for the presidential election in France?"

'Sex appeal'

"Izra," as Izraelewicz was known, hit back: "I get the impression from listening to you that it's obvious that, if we were to call for a vote for anyone, it would be for Hollande. But it's in our interest for Sarkozy to win: he's an unpredictable man, a formidable actor, and I'm not sure that Hollande will have the same sex appeal! The director of [the magazine] L'Obs told me: 'When you put Hollande on the front page, you don't sell.'" Izraelewicz was not entirely wrong. But Hollande was not the only cause. While the paper's sales continued to rise, readers were no longer as interested in politics as they once were. Journalists themselves were less eager to join the politics desk.

In 2017, the election of Emmanuel Macron, a young president who is a good communicator but impenetrable, didn't change a thing. It's as if power has shifted to the economic or media spheres. Political parties are moribund. Within the newspaper, it is no longer necessary to have headed the politics desk to become a director, as was the case for so long. The paper's current director, Jérôme Fenoglio, elected in 2015, has never held a role at the politics desk.